The day kicked off with a sunrise run to the East of Ghent, thanks to a strava route. A pre-set route made it much easier to just run and enjoy the surroundings and a beautiful clear morning, rather than constantly trying to navigate.

Bikes are definitely the preferred and priority mode of transport. Crossings have dedicated bike sections, paths have subtle red indicators to separate pedestrians, and trams, buses and cars are clearly considerate of commuters and kids getting on with their day.

The route took me along the Scheldt River and the tightly packed houses of the city centre made way for units with green space and the occasional detached house. It was nice to see a lot more greenery and wildlife, even though the ducks appeared to be creating superhighways through the current blue-green algae bloom!

We headed to Ypres on the Western Front deep in the countryside, about an hour by train to the South of Ghent. It’s a quiet little town, that is significant in Australian and Commonwealth WWI history. There are many things that put towns on the map to attract tourists, this is not one that any town would aspire to.

After whizzing through miles of fields in the rain, we enjoyed the walk along quiet streets into the town centre. This time, the wooden doors caught our eye, so similar to a lot of the old Belgian style furniture that filled my Grandmother’s house, and then ours.

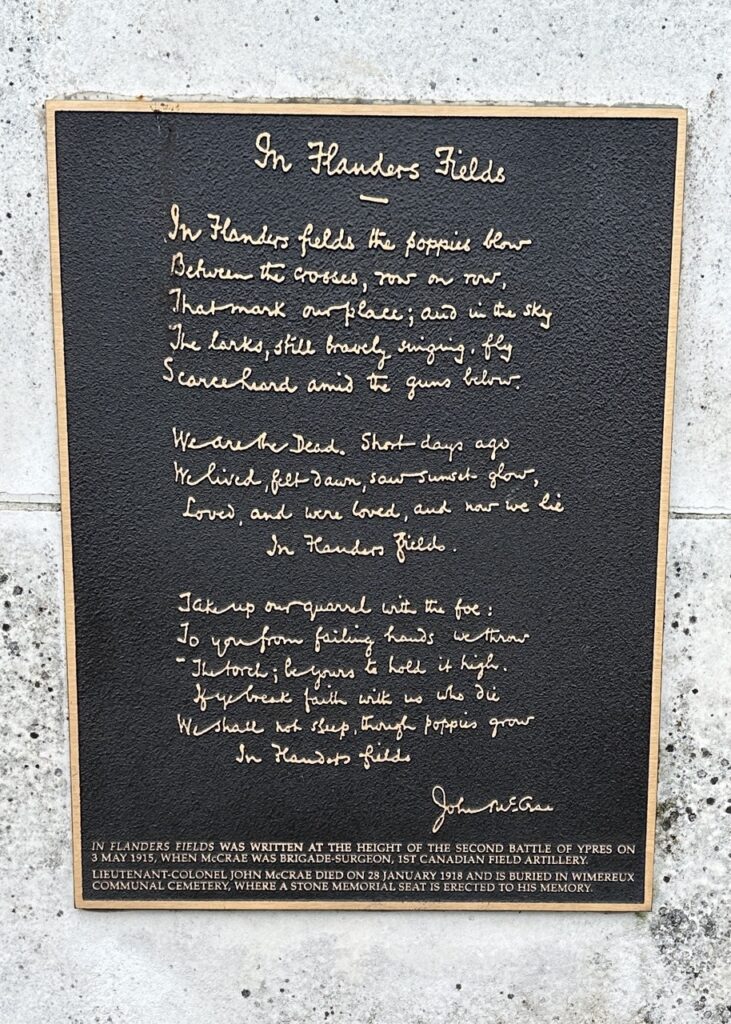

Our Battlefield tour focused on the North Salient with our guide Andre, who had spent his career in the Belgian Army – first as a soldier, then as a historian before becoming a tour guide in the area. We started at Essex Farm, the site where John McRae wrote the poem ‘In Flanders Fields’, the day after one of his good friends died at the beginning of the Second Battle of Ypres in April 2015.

The poem has become synonymous with WWI battles on the Western Front, with kids across the Commonwealth learning it in school. From Andre’s perspective it was propaganda – particularly the third verse – hiding the terrible reality of the war, and painting a positive picture that would encourage mothers to let their sons sign up. Maps of the battlefields also didn’t show cemeteries, hiding the significant losses from all but the medical teams.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

As a Doctor, John McRae led the field ‘hospital’ at Essex Farm. The single bunker where he worked to save the lives of injured soldiers remains today. It was tiny, dark, and often flooded. Anaesthetic was reserved for those who were likely to pass away from their wounds, leaving others in horrific pain. The conditions and experiences of these men are unfathomable.

The Essex Farm cemetery is small and neatly placed on the roadside. Soldiers were buried where they lay wherever possible, so some headstones sit at 90 degrees to others, and others are condensed to mark mass graves. The cemetery contains the remains of the one of the youngest casualties of war – a boy just shy of 16, who lied about his age to enlist.

Our next stop was Langemark German Military Cemetery where 44,000 German and 2 British soldiers are buried. The area is near the site of the first poison gas attacks by the German – a hideous form of warfare that led to the invention of the gas mask. It’s also the site of German propaganda – images of German schoolboys appearing to run happily to the front line belied the truth of their experience as they charged to their deaths. There are 3,000 students buried in Langemark.

The cemetery has a distinctly different style – black stones mark individual graves, alongside the comrades’ grave which contains nearly 25,000 soldiers. The names that are known appear on tombstones surrounding the space, while a sculpture of four mourning figures looks on. It’s a dark and sombre space, surrounded by the samefields that contain the graves of their enemy.

As you drive around this area it’s so hard to imagine what took place here. The respect for the fallen is clear – cemeteries are well kept, and farmers maintain space around those in the middle of fields. While it was one of the most dangerous places to be in WWI, it was one of the safest in WWII as Hitler had ordered that no monuments would be destroyed or damaged. Remains and ammunition continue to be found, and teams relentlessly seek to identify and honour the fallen. The memorial to Canadian soldiers at Sint-Juliaan recognises the loss of 2000 soldiers in 2 days in April 2015, as well as respectfully telling the story of the battle.

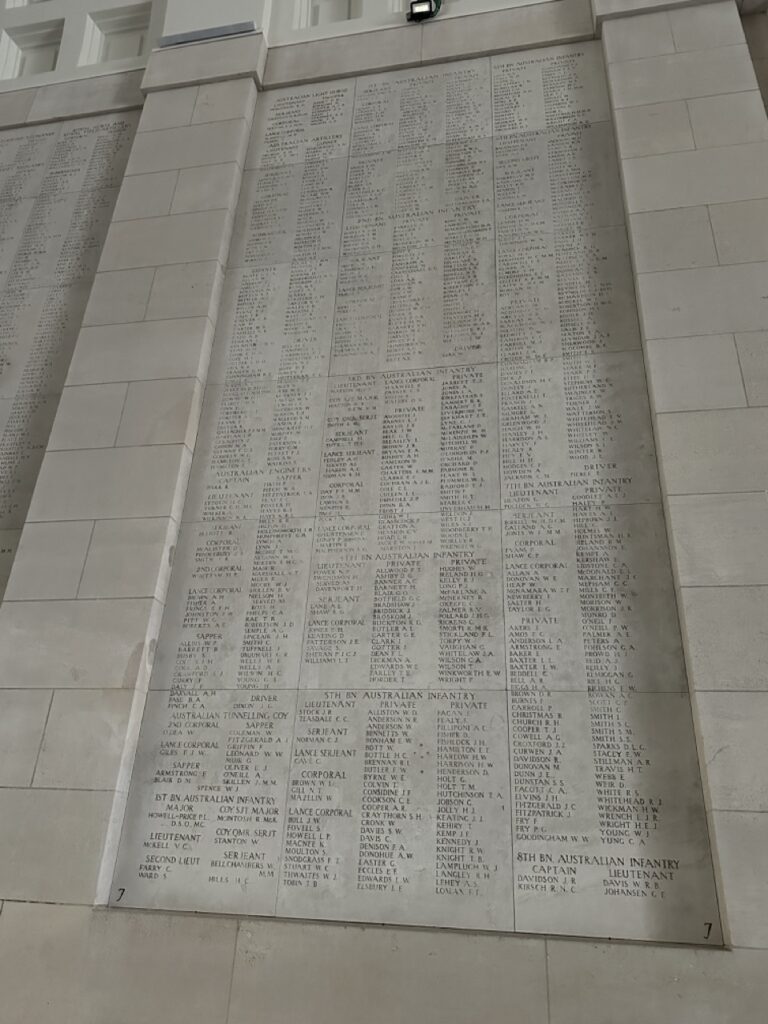

Tyne Cot is the largest cemetery for Commonwealth soldiers in the world. Like all the cemeteries in the region, it is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. They are consistently beautiful, respectful, and cared for. The Cross of Sacrifice sits in the centre, with the headstones organised in the form of a parade ground. The walls around the sides form ‘Memorial to the Missing’ containing the names of the 35,000 British and New Zealand soldiers who had not been found by August 1917. It’s huge.

There are 12,000 headstones in the Tyne Cot cemetery marking the places where a soldier was identified. The scale of the cemetery surrounded by fields is incomprehensibly vast. To put it in perspective – 250,000 Commonwealth and 249,000 Germans soldiers died in the area. That’s the equivalent of 19 per square metre.

…and still, every one of those soldiers is a story – a son, brother, father, friend that is loved and missed. How on earth did we end up sending the next generation to war so soon?

The Scottish memorial is another that sits between a small road and some fields. Again, small and respectful, acknowledging all the Commonwealth soldiers that fought so far from home.

We finished our tour with a visit to Hill 62, a war museum that has retained some of the original battleground trenches and craters left by the shells. The conditions were awful and terrifying, with many soldiers lost to illness rather than battle injuries.

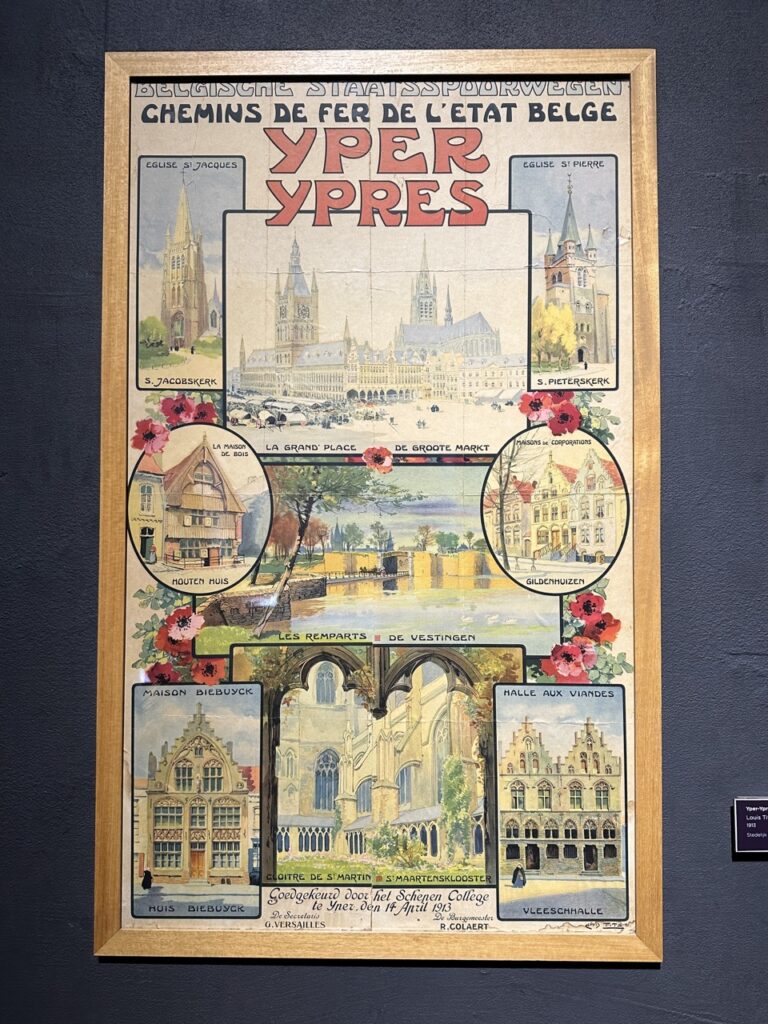

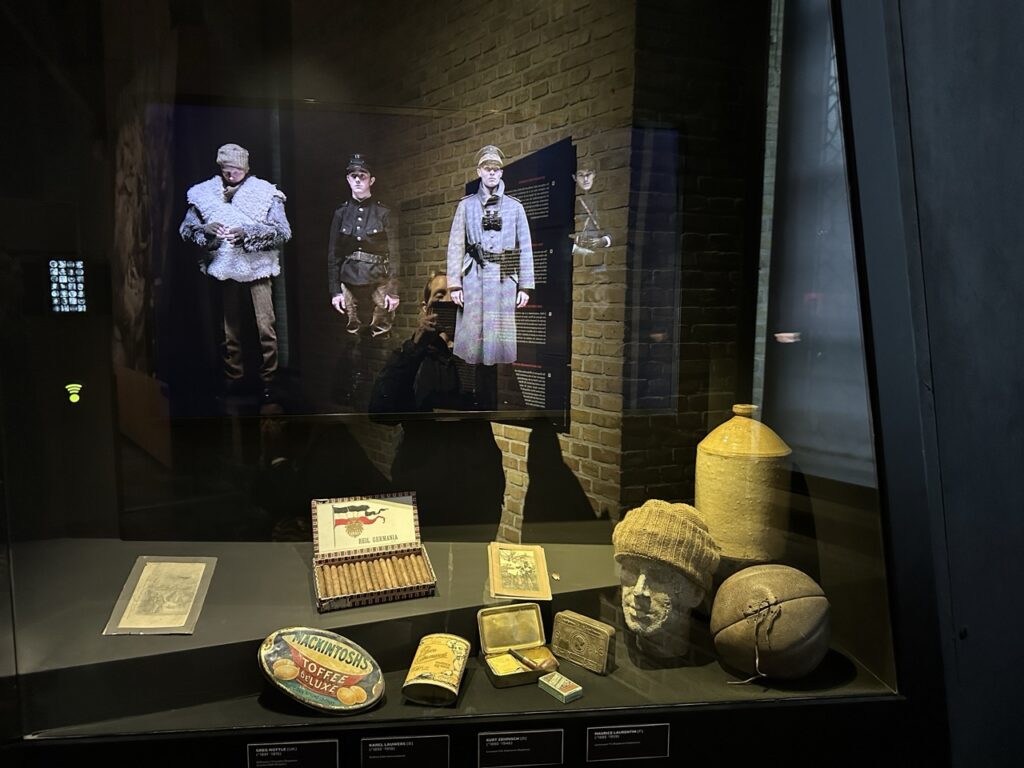

Back in Ypres, we managed an hour in the ‘In Flanders Fields Museum’. This was originally the Cloth Hall in the town and was significantly damaged in the War, while the town was completely flattened around it. Originally it was decreed that the Germans would pay for the rebuilding of the town of Ypres, however this eventually fell to the people of Ypres. The building was reconstructed using all the original bricks that were left, and you can still see the scars and blackened bricks in places.

This space tells the story of the battles in the area from the perspective of the soldiers that fought there. It’s the camaraderie of the ‘Christmas Truce’ and united forces, as well as the propaganda and the battles.

The final stop for the day was Menin Gate, the Memorial to the Missing that contains the names of 55,000 soldiers, including the missing Australians. The Australian soldiers had a significant impact on the area – making nearly 2km progress in one day… while only 4km progress was made in 100 days. Menin Gate is currently under renovation, but the Last Post continues to play every evening at 8pm to remember the fallen. Another mark of ultimate respect.

In some ways our cold, windy, wet day touring Ypres was fitting. This place should make us stop and feel uncomfortable about the world we live in and the atrocities that mankind is capable of. It should also remind us of the deep sacrifice that thousands of men made, and the impact that rippled through families and communities for generations to come.

Lest we forget.

Love M & BBx

Comments are closed